This blog entry attempts to highlight the sorts of products meteorologists will look at and consider when diagnosing whether or not conditions are favorable for tropical system development and/or growth. It's generally a step-by-step process, boiling down the features that we see in the ocean and atmosphere when tropical systems develop and looking at maps of related quantities to gauge how well current conditions match to those features.

First -- what's at the low levels? Using two merged QuikSCAT passes from earlier today, the 850mb streamline analysis from (http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/tafb/QUNA00.jpg), and the latest SST map across the region (see http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/aboutsst.shtml), I've created this composite map of what we have out here:

Red denotes trough axes; in blue are the 26C and 27C SST isotherms. Note the low being on the cyclonic shear side of what I'll call the low level westerly jet. This is a favorable position for development/maintenance of the low feature and this setup is somewhat akin to a monsoonal trough. The SAL does not appear to be a concern in hindering anything out there right now.

Shear maps from the Univ. of Wisconsin site suggest ample shear south of 10N, but I think this is being somewhat skewed by the westerly LLJ located underneath the African easterly jet at 600-700mb; underneath the subtropical ridge, winds are fairly favorable. Compare the following two images from the Univ. of Wisconsin site, first the deep layer wind shear (upper levels minus low levels) followed by the mid level wind shear (mid levels minus low levels).

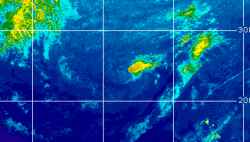

Note how 30-40kt of mid-level shear shows up as merely 20kt of deep layer shear; this is because of the strength of the African easterly jet in feeding these waves at mid-levels coupled with the westerly LLJ providing an ample source of vorticity at low levels. Simply put, shear is not really a concern. So, the majority of the necessary underlying conditions are present for tropical cyclogenesis, but there are two key factors holding things back: SSTs and low level stability. As discussed in my "Slow start to CV season ahead?" post from last week, the SSTs out there are chilly (both overall and compared to climatology) and there is still significant low level stability underneath the trade wind inversion associated with the subtropical ridge, quite possibly being fed by the cooler SSTs. Compare the composite map above to a current IR satellite image from the region:

Indeed, it's not merely coincidence that regions of cooler SSTs and the more stable environment match quite well.

Putting it all together, the CIRA/SSD tropical cyclone formation probability product (see http://www.ssd.noaa.gov/PS/TROP/genesis.html) shows fairly high (climatologically speaking) probabilities of formation in the Eastern Atlantic. Looking at the individual components, however, there is one that sticks out like a sore thumb in limiting these probabilities from being even higher: yes, it's the low level stability. The genesis threshold is >-8C, so it is above that, but it is nothing like what is observed further west in the basin. Vertical instability is crucial to convective growth and, ultimately, organization and development.

Overall, as I've noted before, if anything can stay south of 10-11N, it's got a pretty favorable environment. Otherwise, it seems as though 45-50W is a more likely location for genesis than the deep tropical Atlantic.

So, I wonder out loud, could this wave, rather than being one to develop, be the one that provides enough ambient vorticity and "oomph" (for lack of a better term) to precondition the low levels in the eastern Atlantic for future developments? That inversion can be weakened from below as well as it can from above, including through mixing processes (e.g. by the wind) and heating processes. The models, particularly the and the , are sensing that overall, conditions are pretty favorable for development. They may not be handling the low levels quite as well as we'd like, though, given the relative lack of available data in the tropical east Atlantic. The result is a strong genesis signal, but one that may need to be muted just slightly.

Still, as long as these types of conditions hold within the basin, we're going to have to keep a very close eye on what is going on out in the Atlantic. I hope this has been a somewhat useful guide both to what is currently occurring within the basin as well as to the overall process of tropical weather forecasting. If you have any questions, please feel free to ask them in the "Blogger Discussion Forum" and I'll do my best to tackle them!

--------------------

Current Tropical Model Output Plots

(or view them on the main page for any active Atlantic storms!)

|

Threaded

Threaded